Wiki: “a risk-neutral measure is a probability measure such that each share price is exactly equal to the discounted expectation of the share price under this measure.”

This article gives a practical and fun explanation of the concept. Summary: financial derivatives can be replicated using “tradable assets”. In the world of options, those are vanilla options. The risk-neutral measure refers to the probability distribution of those vanilla options’ prices (= probability that the underlying reaches a certain level).

Illustrative example 1: lottery ticket

The author mentions a nice lecture from Bruno Dupire to grasp the concept of tradable instruments. More specifically, he highlights an interesting paradox on a lottery example; two logics could be used to know whether the lottery ticket is cheap or not:

-

logic using the expected value

-

logic using the replicability (risk neutral case)

Illustrative example 2: butterfly prices

The author shows that, based on prices of vanilla options, we could draw the prices of butterflies. This shows that pricing an exotic payoff relies on the prices of tradable instruments.

Now those prices follow a distribution that actually represents the probability that the stock reaches a certain level. This probability distribution is the risk-neutral probability. The author also proves that it’s indeed a probability distribution since integral = 1.

Tentative definition: the risk-neutral measure is the probability distribution of the tradable instruments so that their prices are as such. Put it differently, it’s the probability distribution of the tradable instruments so that NFL (no free lunch) holds. As the author mentions, we need this risk-neutral measure because “we’d like to price […] derivatives in a consistent way with those [ndlr: vanilla products] that we can see to prevent making arbitrageable prices.”

Under Black-Scholes, the risk-neutral distribution is lognormal.

We can also say that the risk-neutral probability is the implied probability so that there is no possible arbitrage. E.g. let’s assume a call fly pays out 1 when it finishes at the level $K$ and costs 10%. The implied risk-neutral probability is thus 10% (= the probability that the stock finishes at $K$). With this probability, the price of the instrument allows no possible arbitrage. If the implied probability would have been 20%, we could have bought it and, based on law of large numbers, make some gains on average.

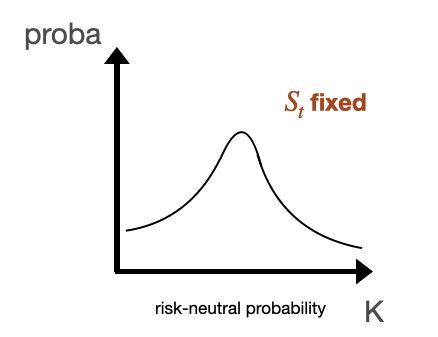

The risk-neutral probability is typically displayed for a range of strikes, but in practice it just reflects a certain level of price at maturity. The reason is that the risk-neutral probability is deduced from observable prices that are for different strikes and a fixed spot. The fat tail should be interpreted as: “there is a larger probability to have extreme low prices than extreme large prices”. See options section for more details.